Understanding STARKs from scratch with high school math (Part 1)

I assume you've already heard about STARK (Scalable Transparent Argument of Knowledge) somewhere. Here is the quick recap.

Prove a computation without needing to execute it again to verify it.

Thanks to this you'll be able to:

1. Make the verification faster than executing the whole program

2. Hide some inputs to the verifier (a witness)

The toy problem: Deterministic Finite Automata

During this series of articles we will be playing with a simple but still useful example: Deterministic Finite Automata (DFA). The name might be scary, what is even an automata? But In reality it is a simple tool to check properties on a string.

More formally an automata is a tool that answers true if a word is in a rational language and false if not.

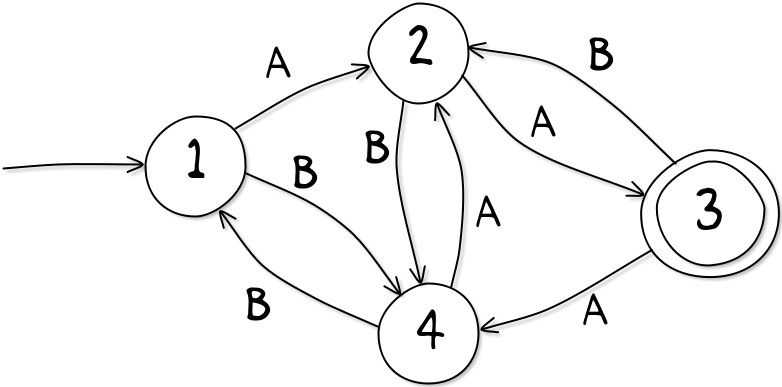

For example this automata, you start on the node 1 and travel through the automata depending on the word you are inputting. For example the word BBABA ends at the node 2. Because

\[1 \overset{B}\to 4 \overset{B}\to 1 \overset{A}\to 2 \overset{B}\to 4 \overset{A}\to 2\]

In this case the state / node 2 isn't an accepting one (circled two times) so the word BBABA is not in the rational language defined by this automata.

More formally an automata is \(\mathcal A = (Q, F, q_0, \delta)\) where \(Q\) is the set of states of the automata, \(F\) the set of accepting states, \(q_0\) the starting state and \(\delta\) the transition function defined by: \[\delta: (q,e) \in (Q,\Sigma) \to Q\].

Proving an automata execution with STARKS — What are we even proving?

A rational language can be described by a regular expression or REGEX (the nightmare for any web developer) that looks like this:

^(\+\d{1,2}\s)?\(?\d{3}\)?[\s.-]\d{3}[\s.-]\d{4}$

For example this REGEX describes the rational language of phone numbers so if we build the automata corresponding to this regex (with the Berry Sethi algorithm for example) we can check if a string is a phone number.

What do we prove?

I know a word W accepted by the automata A

Amazing! So I can prove to someone I know a word accepted by any rational language without showing the word. Right?

Almost, one small detail is missing the word is not really hidden here. Instead the statement will be the following

I know a word w accepted by the automata A such that h(w) = S .

Where h is a hashing function (we will be using poseidon).

Alright everything it ready to start STARKing.

STARKs here I come!

The goal of a STARK proof is to prove a program execution and a program execution is totally determined from its trace. A trace being a table of all the "variables" of the program evolving step by step. For example the trace of our automata execution for the word BBABA is the following (Where ε is the empty word):

| step | state | character |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | B |

| 1 | 4 | B |

| 2 | 1 | A |

| 3 | 2 | B |

| 4 | 4 | A |

| 5 | 2 | ε |

Ok it's going somewhere, we now need to prove this trace, but do you know a lot of theorems we could use on tables? Personally no, but there's something way more powerful than tables, let me summon: Polynomials (Don't be scared it's actually not that complicated).

A Polynomial is just a function of X in the form:

\[P(X) = a_0 + a_1X + a_2X^2 + \ldots + a_nX^n\] where \(n \in \mathbb N\) (a positive integer).

Some may have screamed when I said a polynomial is a function (I know it isn't this is just for simplicity)

Ok so let's encode our trace in a polynomial. But a polynomial only returns a single value how can it encode a whole table? Actually, we will have a polynomial per column. So we want to create two polynomials: S and C such that \(S(0) = 1, S(1) = 4, \ldots, S(5) = 2\) and the same for C but to encode characters. Great let's build that polynomial. So we want \(S(0) = 1\) so \(S(X) = X + 1\) works. Now \(S(1) = 4\), for that \( S(X) = 3X+1 \) works , for \(S(2) = 1\) we can use \(S(X) = −3X^2+6X+1\). Great you're telling me, it works but how did you guess that? If the trace is 1000-lines long, how will you be able to compute the polynomial. This problem is called polynomial interpolation and a very smart guy at the time solved for us: Lagrange.

\[ P = \sum_i{y_iL_i}\] where \[L_i = \prod_{j \ne i}{\frac{X-x_j}{x_i-x_j}}\]

This polynomial is the unique polynomial of degree (n-1) interpolating the n points \((x_i, y_i)_i\).

We now have two polynomials the caracter polynomial and the state polynomial where \(C(i) = c_i\) and \(S(i) = s_i\) where \(s_i, c_i\) are the state and character at step i. Great now we send those to the verifier and it can check whether the automata was run correctly? Not really, first sending the polynomial is equivalent to sending the full trace (depends on the representation actually) so it is not really scalable, and then the verifier knows all the trace so it is not really zero knowledge. So what was that for then? The real magic of polynomials intervenes with the contraints.

Polynomial constraints

A polynomial constraint is a constraint made of polynomials. What is a constraint then? A constraint is an assertion on your polynomials for example assert that you polynomial cancels (equals 0) on certain points. But our constraints will be a little bit more complicated.

Basically, we will write polynomial constraints asserting that the automata has run correctly. This step of writing the constraints of a problem is called Arithmetization and the result of that: the constraints is called an AIR (Arithmetic Intermediate Representation).

Before starting we just a small theorem of polynomials

\[P(x) = 0 \iff (X-x) \text{ divides } P \iff \frac{P}{X-x} \text{ is a polynomial}\]

What is a valid automata execution?

Try to guess it as a exercise.....

An automata execution is correct if and only if:

- it has started on the initial state

- it has ended on an accepting state

- each transition is valid (\( \delta(q_{i}, c_{i}) = q_{i+1} \)

To translate this into polynomials, a constraint is valid if and only if it is a polynomial.

So if we translate the automata constraints in polynomials we have:

- \( \frac{S(0) - q_0}{X-0}\)

- \( \frac{\prod_{q \in F}{S(n-1) - q}}{X - (n-1)}\) where n is the number of steps and \(F\) the accepting states

The last constraint is a bit more tricky because we need to check for each step that the state[i+1] is equal to the result of the transition function called with state[i] and character[i]. For that we first need to encode our transition function as a polynomial. The problem is that the transition function takes two parameters and multivariate polynomials are more complicated so we need to find a smart trick to use. This trick will be explained in the next article (let's assume for the moment that we have multivariate polynomials).

\[ \text{ step polynomial } = S(X+1) - \text{transition polynomial}(S(X), C(X))\]

This polynomial is equal to zero when the transition is valid. And we can transform it into a constraint:

\[ \frac{\text{step polynomial}}{\prod_{0 \le i \lt n-1}{(X-i)}}\]

We now have all the constraints ready proving the execution correctness. The next article will dive deeper on what to do with those constraints.